By Abigail Stoff

As a future librarian, I am very interested in the reading habits of students. People have told me and friends of mine “if only you read more …” fill in the blank. Julie Gilbert and Barbara Fister, librarians at Gustavus Adolphus College in southern Minnesota, were just as interested as I am to know why people believe reading is going extinct with young people and whether or not that belief is true. To try and answer that question, Gilbert and Fister gave surveys to students, academic librarians, and a small number of writing instructors. These librarians and professors were asked about the recreational reading habits of their students and students were asked about their own reading habits. More specifically all participants (including students) were asked how often students read, what they read, and how much they would like to read. Gilbert and Fister found that reading is not voluntarily going extinct. According to their surveys, students enjoy reading for fun; however, they don’t have much time for recreational reading due to the readings and homework they are required to do for class (Gilbert 490).

Gustavus Adolphus College located in Saint Peter, Minnesota.

The survey was conducted at Gustavus college. Students were asked whether or not they enjoy reading (nonfiction or fiction) for fun. Although responses varied across majors, gender, and genre, 93% of overall responding students said that they like recreational reading (Gilbert 478). The results indicate that women are only slightly more likely to enjoy recreational reading than men, which contradicts past findings, such as in Michael W. Smith and and Jeffery D. Wilhelm’s book “Reading Don’t Fix No Chevys”: Literacy in the Lives of Young Men (Gilbert 478). Though there were little differences between gender, there were larger differences between majors. Some students in a particular major reported a much stronger liking for recreational reading, such as the humanities major (99.0%). Some, however, did not like recreational reading as much, such as the pre professional majors. Students were also asked what genres they preferred to read. The favorite genre of students, by far, was general fiction (76.9%) followed by mystery (38.9%) and classics (33.7%) (Gilbert 479). These results, again, varied greatly between gender and major. For example, men are two times more likely than women to read science fiction and natural science majors are “over three times more likely to read science fiction than preprofessional majors” (Gilbert, 479). Plenty of students also like to read magazines, newspapers, and online publications. Just like with genre, the amount of recreational reading done by students varies slightly between majors.

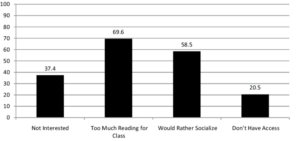

Student responses as to why they don’t read recreationally.

While many students reported that they do enjoy reading recreationally, they also reported that they don’t have much time to read what they would like. Much of their time is spent doing assignments for class. As well ask asking students questions about their reading habits, Gilbert and Fister also asked academic librarians across the nation. When asked how often students come to the library to find recreational reading material, the majority of librarians (61.0%) responded that students only occasionally look for recreational reading material in the library (Gilbert, 481). There are many reasons why students don’t or can’t read recreationally, the main reason, with 77.1% of student respondents agreeing, being that they “already have enough reading for class”. Other reasons being that students “would rather socialize” (35.7%), “would rather spend time in other ways” (31.2%), “don’t enjoy it” (3.3%), or “don’t have access” (3.3%) (Gilbert, 482). As usual, the differences arise mostly between majors. Humanities and fine arts majors report less often that they already have too much classwork. Only 19% of humanities majors report that they would rather socialize compared to the other majors who report in the upper 30%s. Librarians answered similarly, saying most often that students are too busy with other classwork to read recreationally. Another obstacle occurs when libraries don’t have the materials students want to read or the budget to order books for fun. The librarians were also asked whether or not they believe academic libraries should even contain recreational reading materials. Some librarians were of the opinion that academic libraries are “academic” for a reason and that they should only house material related to the curriculum or have only a small number of recreational reading material. Others support having recreational reading sections of their library because of the student demand. Students at Gustavus were asked what the library could do better to get students engaged in recreational reading. The top two options were book lists (60.2%) and an increase in the collection of recreational reading materials (40.5%) (Gilbert, 484).

Folke Bernadotte library at Gustavus Adolphus College.

Since this study was conducted, Gilbert and Fister have made some significant changes to the Gustavus Adolphus college library. Lists of recommended reading lists were made accessible to students in the form of bookmarks and a website will be launched which includes the lists and directions on where to find these materials. The Gustavus library’s circulation policy was also changed so students could take materials home during long breaks after it was found that students read more often during breaks from school. A fiction section that included all of the new book recommendations was also created in a new reading room to promote reading for fun (Gilbert, 489). The library plans on keeping this new section open for another year and advertising it further and getting student feedback. As well as new fiction books, they have also included magazines into their circulation system so students can now check out magazines. The library is also now offering a reading discussion class for partial credit. The library looks forward to seeing the effectiveness of their efforts on student reading habits.

Though the study’s findings are impressive, there are some issues with the study that the authors do not address. The majority of the study was conducted at only one small college. The results would be more valid if the study was broadened to multiple colleges. Having a small sample size could more easily skew results than having a large sample size. The survey was also written by the academic librarians at Gustavus. The librarians, biased as to what results they want, could have unconsciously worded the survey to sway respondents to answer in a particular way. Even the fact that the student survey was given to students by librarians could sway the students to respond how they think the librarians want them to respond. In order to avoid this, the survey should have been given to students from a neutral third party. The survey given to professors was only given to english professors and not professors of any other subject. English professors could be biased toward the reading habits of college students, which again, could skew results. The survey should have been given to professors of all subjects, not just English professors. This would give a more diverse, and therefore more valid, answer to what professors think of student reading habits.

This study has found that reading among students is, in fact, not going extinct. The previous studies that have concluded that young people don’t read also don’t take into account required class reading that students do. When we take required reading out of the equation, it is easy to see why those studies would believe that students don’t read. It is because students don’t have time to read anything other than required reading. However, this study proves that students do enjoy reading and would read voluntarily when they have the time and when they are interested in the material.